A new CBC Short Doc, “Patty vs. Patty” is a delicious recounting of the time the Canadian government tried to prohibit Toronto’s Jamaican bakeries and restaurants from selling beef patties.

In truth, it wasn’t the retailing of this beloved Jamaican snack that the government objected to, but its name.

It all started back in a seemingly simpler time––1985––at the Kensington Patty Palace, a Jamaican family bakery on Baldwin Street. One cold February day, while the owners, Raymond and Pat Davidson, were on a visit to Jamaica, their son and store manager, Michael Davidson, received a visit from a food inspector from Consumer and Corporate Affairs.

Instead of ordering one of the Patty Palace’s freshly baked namesake snacks, the official informed Davidson that he was in violation of the law for illegally using the name “patty.” She gave Davidson a three-month deadline to remove the offending “patty” from all signs, menus and packaging. If not, the business would be fined $5,000 (equivalent to $11,000 in 2022).

At the time, as defined by Canada’s Meat Inspection Act, a “beef patty” consisted solely of ground meat and mild seasoning. According to the government’s classification, a Jamaican patty––spicy beef encased within a turmeric-tinged, flaky pastry shell––failed to meet with established patty criteria. Moreover, the feds argued that the misnomer ran the risk of sowing confusion among hapless Canadian consumers for whom a “patty” was something you grilled and slapped on a bun.

As a result of an influx of Caribbean immigrants in the 60s and 70s, by the 1980s Toronto had become home to quite a few patty retailers. Like Davidson, they were outraged by the government’s blind bureaucracy and lack of cultural sensitivity. They were also adamant that they wouldn’t change the name of their iconic dish. It wasn’t just that the alternatives suggested by the food inspectors––turnovers, meat pockets, Caribbean pies––were woefully unacceptable. For many, the cost of changing all the signage and registering a new business name would be far greater than the threatened fines.

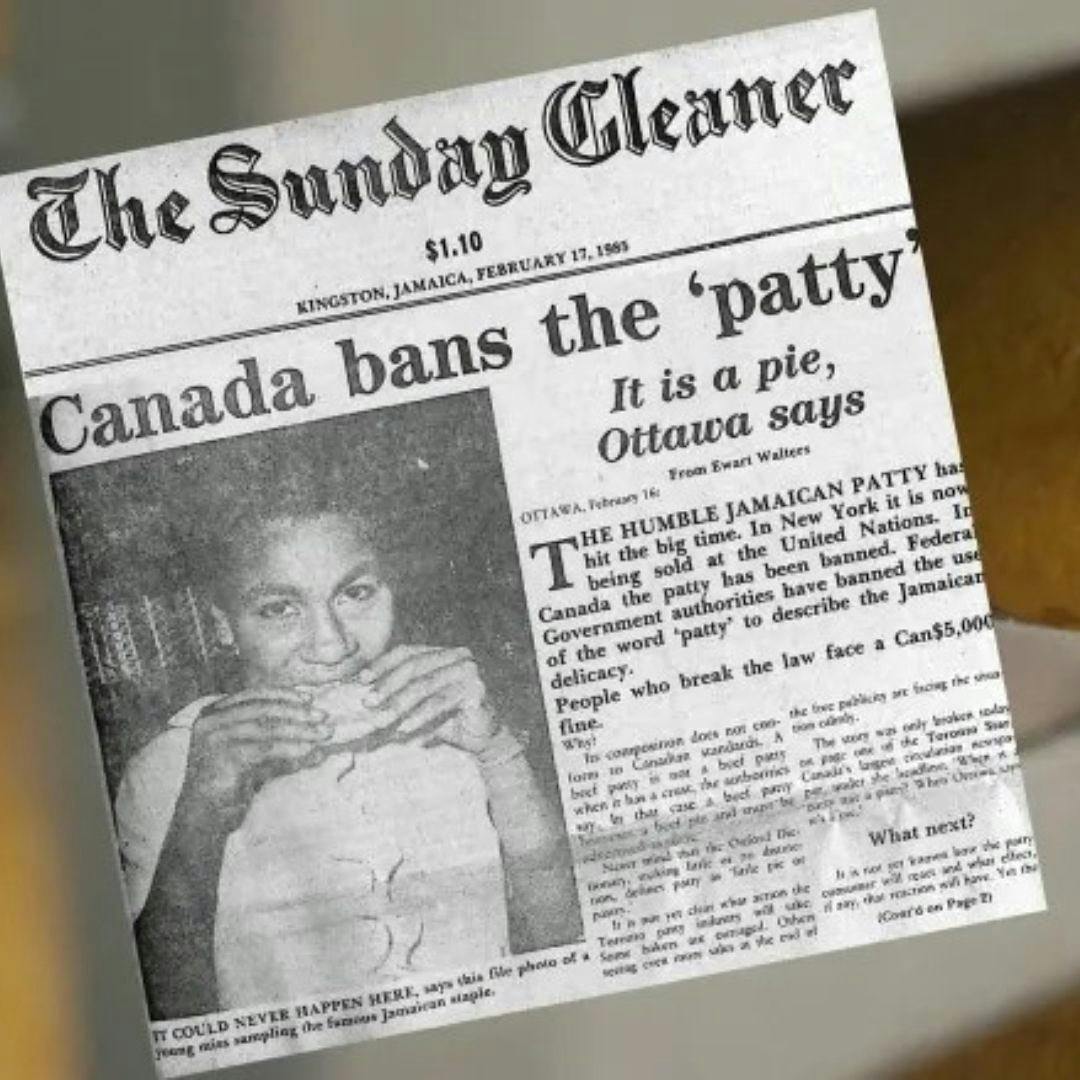

As Toronto’s Jamaican community rallied, Davidson found himself playing the role of leader and spokesperson for the resistance. Within days, media, lawyers and politicians became involved in the escalating “Patty Wars,” which awkwardly broke out just as then Prime Minister Brian Mulroney was planning an official visit to Jamaica. Davidson’s renown grew to the extent that one morning, his parents opened the local Jamaica paper and were surprised to find his name beneath the front page headline: “Canada Bans the Patty”. In the meantime, in solidarity with the cause, the Patty Palace’s sales soared.

In late February, Davidson was present at the historic “Patty Summit,”, where members of the resistance met with bureaucrats to iron out a compromise. In the end, all parties reached a happy agreement. From that moment forward, in lieu of “beef patties”, vendors would refer to their products as “Jamaican patties.”

This little-known, but tasty slice of Canadian culinary and cultural history was so ripe––and ridiculous––for the telling, that when Toronto filmmaker Chris Strikes stumbled upon it in 2020, he couldn’t resist pitching the idea to CBC. With the project greenlit, Strikes coaxed Davidson into providing engaging tongue-in-cheek narration, and mingled media footage from the time with dramatic, albeit slyly satirical, reenactments of key events.

Unsurprisingly, all the uproar generated from the “Patty Wars” proved to be good for business, with a multitude of Jamaican patty retailers earning renown throughout the city. Although Kensington Patty Palace closed shop, Davidson opened a much larger patty plant in Scarborough, where, somewhat ironically, he now exports patties back to the islands.

According to Davidson, Toronto presently sells more patties per capita than any other North American city. And each Feb. 23, the city celebrates Patty Day. As proof of how deeply integrated the snack has become in the city’s foodscape, nobody refers to it as a “Jamaican” patty anymore.

Produced by Maya Annik Bedward and Kate Fraser, the 18-minute doc is available for viewing on CBC Gem and YouTube.